Discover rewarding casino experiences.

|

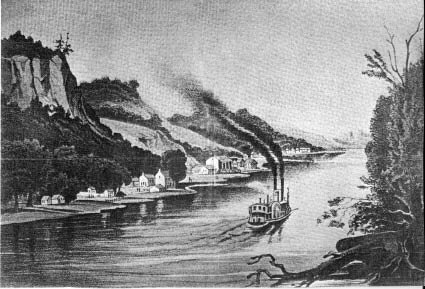

Then just prior to mid-nineteenth century, the “moving picture” came to be, first being preceded by the cosmoramic view, the cyclorama, the panorama and THEN the mobile panorama. There weren’t many of them but if a place you knew or had heard about, Savanna, for instance, and its neighboring towns up and down the Mississippi you made an effort to attend. You could ooooh and aaah over buildings you might recognize or know someone who frequented the scene. That was entertainment. Those gigantic canvas were mounted on huge wooden frames, two heavy duty poles as reels were fit upright from the canvas to wind and unwind on. A horizontal beam across the top had small wheels with grooves fastened by rope to that beam which guided the canvas along. The poles/reels that moved the canvas were revolved by a gear system turned by hand, of course. It took many hands to make a moving picture. Imagine wrestling that heavy, heavy canvas, yards and yards of it, along with the frame at every venue. But it was worth it to make it reveal those scenes slowly to an eager public who might be encouraged to GO WEST or at least appreciate Ol’ Man River, the favorite topic of seven of the panoramas, and favorite of the public. Although Henry Lewis was long credited with being THE moving picture panoramist, deeper research into the subject has found that there were others before him and artists more successful. The reason he was more noted was that he left behind many diaries, sketches, notes, correspondence that gave insight into method as well as description of the towns along the way and the people who resided on the river. He was an appreciator of people and their uniqueness. Henry Lewis was born in England in 1819 and at age ten with his father, Thomas, came to Boston where he was indentured to a carpenter. A few years later he and his father traveled to St. Louis where his brother George lived. Henry got a job as a stage carpenter and scenery painter at the St. Louis Opera House. By 1845 he was being noted as a “landscape painter of more than ordinary merit.” At about that time the idea of painting the entirety of the Mississippi River Valley began perking in Lewis’ head. It was he, it has been suggested, who gave John Banvard the idea and who did paint the lower Mississippi, St. Louis to New Orleans (last week). Banvard had since childhood desired painting the biggest painting in the world. Here was a subject that could inspire it. He was very successful financially and in drawing crowds that exceeded a million viewers, here and abroad. Henry Lewis ascended the Mississippi three summers, sketching scenes and making notes. On the third summer he was prepared to begin the final stage. He hired a couple artists to assist him plus John Robb, a St. Louis newspaper man, accompanied the party to help write the narrative that would accompany the moving picture and to do advance publicity. There were, of course, the necessary labor to pole the boat and set up camp, etc. The mode of travel on the water was not your common sight. Lewis bought two of the largest canoes he could find, two fifty footers, onto which he fixed two heavy beams three feet apart. His carpentry skills came in handy here when he built an 8 foot by 11 foot platform on the beams and on that constructed a cabin into which bunks and bins were added. The cabin roof was flat so that Lewis could set there to sketch and make notes of the passing scene. Sails and a jib were to aid in motive power as well as poling the cumbersome ark. He named it the “Minnehaha.” Lewis had left St. Louis June 14, 1848 aboard the steamboat, “Senator,” captained by one of the most well-known steamboats man of the time, Daniel Smith Harris of Galena. It is reported that Lewis paid his fare by painting a picture for Harris that was passed down through the family afterward. He kept notes throughout, describing the countryside and the people whom he’d met as well as seeking out. The boat stopped for a short while at Nauvoo, the capitol of the Latter Day Saints. He had no time then to sketch their Temple that was being constructed but did so on the descent and which was made into an engraving. John Rowso Smith also did an engraving the Mormon Temple for his panorama which preserve its image after it was destroyed by fire by arsonists. On arrival at St. Paul, the “Minnehaha” was constructed and preparations made for the unique journey. The odd contraption, by the way, served them well on their down river voyage but at arriving at St. Louis in the fall it was anchored at the shore when the Great Fire of 1848 destroyed three hundred homes, twenty steamboats and the ark of Lewis’ voyage. He did picture it in a few of his sketches for our appreciation. The Great Fire was subject of one of Lewis’ excellent abilities ... The “sissolving view,” that was a “before and after” of a scene ... The city as a whole, then that destroyed to ashes, segueing one to the other. His perception of places and people crowd his diaries. At Prairie du Chien he noted the “quaint chateau and picturesque cottages of the French traders and trappers who’d settled there as early as 1734” to make it one of the oldest villages on the Mississippi. Down river they had trouble finding the proper channel to go up the Fever River to Galena there being so many bayous or swamps at their confluence. After a dead-end, they finally found their way to the lead capitol of the Midwest, or rather, the entire of America at the time. The party was hosted at the American Hotel at Galena by a friend from Ft. Snelling and Capt. Daniel Smith Harris urged them to be his guest for two or three weeks but they were unable due to the press of time. They went down the Fever River that night to camp and were nearly swamped under by a steamboat under full power passing them in the dark. While at Galena a Mr. Rogers joined them. He had been hired to sketch scenes to assist Lewis in the preparation of the panorama. The passing scenes were going by too speedily. Reaching the Mississippi from the Fever River they hailed the last settlements straggling down from Dubuque where when they’d stopped and were pleasantly surprised to find had two newspapers “out here in the wilderness.” Lewis in his journal noted the burial site high on a bluff top of Julian Dubuque who’d so early settled there by the mighty river—the 1600’s. Down river he reported on the “beautifully situated” town of Bellvue, 150 residents (the 1850 census, however, reported 360!). He briefly reported about the “Bellvue War” just a few years before when the “banditti” — a gang of horse thieves, counterfeiters, murderers, had control of the territory. It was they who murdered Col. Davenport at Rock Island. No mention was made in his diaries of Savanna although its site below the bluffs, the “Palisades” is reported. You Savannans might pick out a few of the buildings depicted. The picture was printed in “American History Illustrated, 1982” from a painting on view at the Minnesota State Historical Society, a wonderful object. Just prior to their sailing past the Carroll County town they’d stopped in a heavy rainstorm along shore at a pair of cabins one of which was occupied by a Scotsman and “his intelligent lady,” he a former British naval officer. They had a fine bottle of wine and excellent conversation, another bonus there on the frontier, something Lewis noted and appreciated about the America he’d come to know.

Passing Savanna they came to two “beautifully situated towns,” Fulton and Lyons, opposite one another. “The river here is very narrow but deep with rapids. It has the name, the “Narrows” of the Mississippi. We made forty-eight miles today. Nothing of particular note occurred after passing Galena. The signs of civilization begin to increase. The pioneer’s log hut is replaced by the comfortable log house and the small, poorly cultivated field that compels the farmer to labor in gives way to larger farms and more smiling meadows and fields. We were visited at this place by some of its inhabitants and I learned that the country back (of the river) was of exceeding richness; that it was fast filling up. There were little rival towns (between them the most Christian and city-like hatred existed). They were beginning to flourish. These towns were built by rival speculating companies more than ten years ago and like men who grow very fast, they were not strong or healthy. The consequence they outgrew their clothes; huge taverns were had no one to eat in them. Towns of fine houses had no tenants but that which heals all diseases either by killing or curing is fast filling up numerous towns on the Upper Mississippi and depending on their own resources and the wants of the country surrounding them, they will fast become what they all intended to be, cities.

|