Discover rewarding casino experiences.

Please Don't Quote Me Even supermarkets have history. And it extends back farther in time than you might believe. |

Hamlets inevitably grew at rivers and streams where mills were built or at busy crossroads where neighborhoods developed, an American hallmark. Of course, general stores and tradesmen were among the first to spring up. One of the first to be recorded though pieced together from newspaper clippings; brief mention in county history, word-of-mouth, letters and journals (!) was a “chain” formed by John Meeker in upper New York state at the dawn of the 1800’s, early nineteenth century. Back then there probably was no such name as “chain” in regard to business or the idea of one, but Meeker was an able entrepreneur who had a penchant for developing the general store. In all he probably had fifteen such. Besides choosing excellent trading sites, he was skillful in finding capable and clever young men to manage each. He made them junior partners instead of paying a wage, that to keep them more interested in sticking to the job because the profits that accrued would be to their advantage ... The partnership was incentive. John Meeker attended to the trade and bartering that was a major portion of a general store’s business. Corn, wheat, potash, wood, even some livestock and many more items were under Meeker’s supervision. He would travel by four or six horse-drawn wagons to Albany on the Hudson to exchange the produce for hardware, dry goods, groceries, drugs and all the hundreds of things general stores kept on shelf. From some of Meeker’s stores the trip took two weeks. Ironically, John Meeker himself did not wholly succeed while some of his “partners” did. In his old age Meeker had overextended himself to become an insolvent debtor to retire on his farm One of his successful former partners, however, became something of an entrepreneur also, although he did not organize one of the first “chains” as Meeker had done. Jedediah Barber had been chosen by Meeker to manage one of the stores, this in about 1805 or thereabouts. That at Onondaga Hill, New York where he stayed but a few years before he quit to go in business with his brother-in-law, a blacksmith. But as reference stated, storekeeping was in his blood so he returned to a general store, likely about 1811. He, like his mentor, bartered and traded skillfully using, for instance locally grown flaxseed, an important crop at the time, it in exchange for the cash reserve he needed to buy the merchandise necessary.

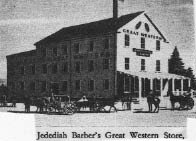

October 21, 1815 5000 Bushels; Flax seed Wanted The subscribers would inform the public that they carry on the business of Manufacturing Lindseed Oil In the village of Homer where they will pay the highest prices for Flaxseed in exchange for Oil, or in Goods at Jedediah Barber’s Store or in Cotton Yarns and Goods at the HCM Company Store. R&H Bishop Jed Barber’s store at Homer, New York was known as the “Great Western.” It was regionally famed and popular. It prospered. When it burned in 1856 it was said to have $50,000 in merchandise at that store alone, quite a figure for the times. It was have discouraged some but Barber with his son, George, rebuilt and opened again in just a few months. It is pictured here from an illustration in “Over the Counter Or On the Shelf” by Lawrence Johnson, along with the excerpt above. It is believed that Jed barber who became a banker in his later years and Homer, the town, were the pattern for the radio serial, “David Harum,” the story of which is found here separately. While John Meeker’s chain store idea may have been practiced by others at that early time, their story isn’t all that well-known. If there were other storekeepers that had more than a few market sites we’d be glad to read of them. And the inspiration their developers gave to subsequent managers like Jed Barber who with his son served, too, as apparently a stiff rivalry for a pair of brothers who created a chain of some magnitude with tea as the product with which they challenged one another. The Barber team, father and son, are to be credited for their energy and creativity in a time of difficult transportation conditions and the lengths of time it took to receive goods, etc. The “Great Western” was a great example of the American idea being put to the test with diligence, new schemes, hard work and a readiness to try different things. Advertising was a must for the “Great Western” which in 1867 used the following in their competition with a major rival in the selling of tea, “The Great American Tea Company.”

The Great Western offered a “Superior Quality Japan Tea and China Young Hysen Tea at $1.00 a pound, warranted as good as any that can be purchased for the American Tea co. at $1.25, or Money refunded. All other qualities same proportion.” Perhaps it was the formidable rivalry that goaded the Great American Tea Co. to excel in its future expansion to hundreds of “chain” stores. Jed Barber didn’t live to see that rise in the storekeeping success of the competition, not even their name change in 1870 to Great Atlantic and Pacific Tea Company. Remember them?

|